A conversation about the future of the LA Times and local journalism

The Southlander interviews journalist Matt Pearce, former head of the LA Times News Guild.

🟢 But before that, some updates from us:

We’re gearing up to publish our very first investigative story. We can’t say too much just yet… but it opens with an obscure cable TV show Donald Trump guest-hosted nearly 15 years ago. From there, we follow a trail of money from the pockets of lobbyists to courtrooms to the region’s oil and gas fields and beyond. There are cagey politicians, toxic chemicals, and even an explosion with a dirty little secret to tell. 🤫

We also just joined The Tiny News Collective! Being a part of this community of news makers is empowering us to access resources like Lawyers For Reporters and tech help for our website. But the best part is being in collaboration with other newsrooms – we’re committed to sharing what’s worked for us and learning about what's worked for others.

Investigative journalism isn’t glamorous (see picture below). It is painstaking. It's cumbersome. It's time-consuming. Most of us are used to instant gratification, and investigative journalism is anything but that. But it reveals wrongdoing. Exposes corruption. Gives power to the people. Our worker-led newsroom won't just follow the story – we will follow the money, the power, and the silence.

The ask...

↗️ You can help us bring The Southlander to life by forwarding this email to anyone you know who cares about local journalism in the LA region.

The Southlander is independent and reader-supported. We're just about half way to reaching our $2,000-a-month fundraising goal that will let us hard launch the first investigative news cooperative in Greater LA. Please help us get there by upgrading to a paid subscription.

The LA Times is going public?

In 2018, the Los Angeles Times was purchased by billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong with the promise of revitalizing the West Coast's paper of record. What began as a period of optimism for the newsroom after languishing for nearly two decades under the ownership of Tronc has since soured amid controversial business decisions, editorial meddling, and round after round of layoffs.

With the purchase of the LA Times in 2018, Soon-Shiong also pocketed the San Diego Union-Tribune and a smattering of small community newspapers. Since then, he's shuttered many of those community newspapers and sold the Union-Tribune to Digital First Media (whose parent company Alden Global Capital also now owns the Tribune Publishing Company, formerly Tronc).

The LA Times newsroom has been atrophied by at least four rounds of layoffs and buyouts in the last two years, the largest of which saw more than 100 employees axed in January 2024. All told, about half of the 450 journalists that the Times had just three years ago remain. In addition, the newsroom’s union has been working to negotiate a new contract for nearly three years; in that time employees haven’t received a cost of living increase.

The newspaper has also seen a concerted right-wing push by its owner. In October, Soon-Shiong squashed a planned presidential endorsement of Kamala Harris by the editorial board. Soon after, he spoke of instituting an AI bias meter and installed MAGA operative Scott Jennings onto the LA Times editorial board.

Since Soon-Shiong took over the paper, it has not had a single profitable year and reportedly lost $50 million in 2024, prompting prognostications of its collapse.

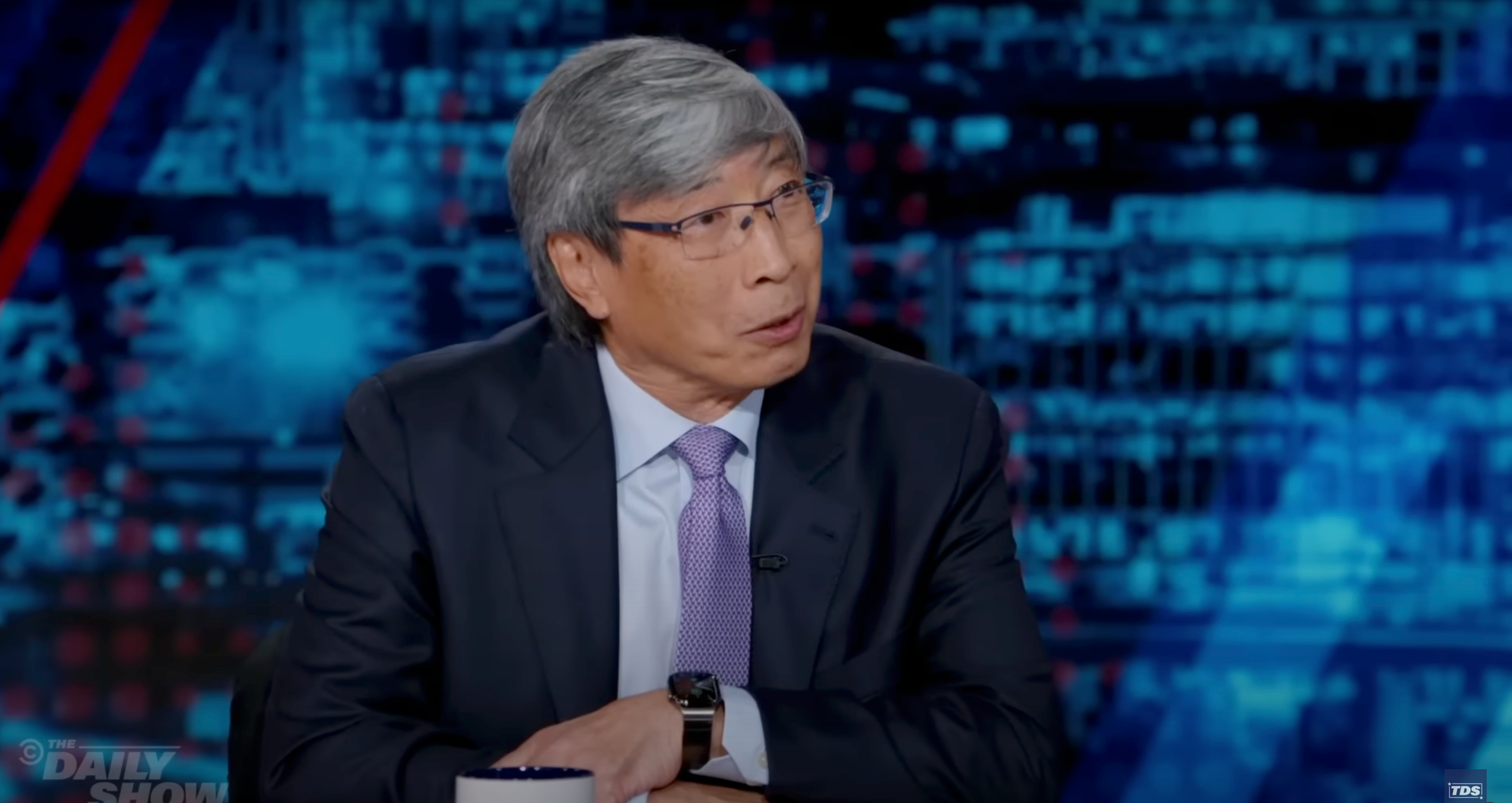

This all led to an announcement Soon-Shiong made on The Daily Show on July 21 that he plans to take the LA Times public. What exactly this means for the future of the newsroom is an open question at the moment.

To help explore that question, The Southlander interviewed Matt Pearce, a veteran journalist who left the LA Times in February and had been the president of the Media Guild of the West, which represents LA Times employees. He recently published a piece titled “What does a publicly traded LA Times even look like?” on Substack. Pearce spoke to Southlander journalist Morgan Keith about his piece and the potential future of the LA Times and local journalism more broadly.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Southlander: Why did you feel it was important to write about what a publicly traded LA Times could look like?

Matt Pearce: So I am a former longtime Los Angeles Times reporter. I took a buyout in February during one of the major recent layoffs at the Los Angeles Times under Patrick Soon-Shiong. Since then, I joined Rebuild Local News, which is a nonprofit policy coalition which works on public policies to support community journalism.

So the reason I wrote about the news of Patrick Soon-Shiong intending to take the LA Times public is because the LA Times, for all its tragedies and shrinking under Patrick Soon-Shiong, remains a pretty important source of original journalism in Southern California. Along with many other local news outlets, it's been covering the immigration raids very aggressively. So the big story about the LA Times over the last few years is what's happened under Patrick Soon-Shiong. He’s a billionaire who bought the newspaper in 2018; sort of rescued it from private equity.

It was good news at first; he spent a bunch of money on the newsroom, hired a bunch of journalists, won a bunch of Pulitzer Prizes for a lot of different coverage in the years since his ownership, but especially since 2020 he's been cutting back on how aggressively he's been investing in the newsroom. And partially that's because the LA Times has been losing tens and tens and tens of millions of dollars. And so I think people don't quite understand exactly how much money Soon-Shiong has been losing on the newsroom, and so it's been shrinking accordingly. Even as he’s been spending a lot of money on the newspaper.

And so that's a challenge for the journalist, because on one hand, he's massively subsidizing the newsroom, and if he stopped massively subsidizing it there would be even more layoffs. But also, change in control for that reason could be interesting. It could be bad, it could be good. His decision, however, to announce that he's taking the LA Times public is very unexpected on one hand, and also, I don't know if it's necessarily a good thing.

SL: From your perspective, as someone who worked in that newsroom and knows it very intimately, how do you think the evolution of its business model towards this public option will impact the journalism the newspaper produces?

MP: So one of the things that's really important for the journalists who still work at the Los Angeles Times is to protect their work from [the] interference to sort of shape the coverage in a way that may be more favorable to Patrick Soon-Shiong’s business interests and political interests. [He’s signaled] wanting to be very friendly to the Trump administration; he canceled a planned editorial board endorsement of Kamala Harris in the last election. The editorial board is actually the place where the publisher, in American journalism, is genuinely, sort of allowed, quote, unquote, to interfere with what they write and to have the editorial page reflect the opinion of ownership rather than necessarily the journalists in the newsroom. But that was something that was a break from how the paper had previously been operated.

So that's something that's very concerning for journalists, because ultimately, the way that we do journalism in the United States, we have a First Amendment that theoretically protects the press from government overreach, but it's only really freedom of the press if you own the press. Journalists in any newsroom across the U.S. don't really own the news organization that they work for. They don't necessarily control the editorial decisions that are made by that publication, even strongly unionized newsrooms like the Los Angeles Times, you don’t necessarily have the legal right to negotiate over the content of the journalism itself. There are other ways that you can kind of put pressure on the organization, but ultimately the legal power resides with the publisher, which is what makes leadership so important.

SL: One of the main protections that journalists have when it comes to having more control over those editorial decisions, despite changes in ownership or public opinion, is our unions, and you're very familiar with that, as the former head of the Media Guild of the West. What do you think that news guilds’ roles will be in the future when it comes to business models that are being developed?

MP: So unions like my old union, are very supportive of, for example, cooperative news organizations getting started. These are newsrooms that are actually owned and operated by journalists themselves rather than necessarily by billionaires or other powerful people. And so one of the last things I did when I was a guild president was to support a grant application for Start.coop, which is a nonprofit organization that helps incubate cooperative businesses across all sorts of different sectors of the economy. We saw up close, you know, the relationship between journalists who are losing their own jobs having the power to start their own newsroom. Because ultimately, whether it's a cooperative newsroom or nonprofit newsroom or you’re a solo creator, journalists still live in American society, you are ultimately operating a business. You need to be able to pay for your rent, for groceries, and to keep doing all the things that you need to do to be able to grow in your journalism. So cooperative business models are one of the ways that are a possibility for journalists to do that.

SL: That's something we've taken into consideration as we form The Southlander. The reality is, a lot of the newsrooms that we have are owned by either billionaires or venture capital firms, and so if we were to see the LA Times go public, the worst case scenario there could be speculation driven by online interactions, especially with a lot of right-wing billionaires like Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, owning those platforms, that they could push for people to invest in these publications in an attempt to influence the editorial direction. Can you elaborate on the potential dangers to the quality of journalism if something like that were to happen?

Help us unleash The Southlander! Our team of talented journalists are itching to start publishing investigative reporting. Help us reach our goal of $2,000 in monthly subscriptions. Paid subscriptions start at only $5 a month and it only takes a few seconds to upgrade.

MP: We live in an attention economy. There are all sorts of places now that are kind of, you know, controlled by right-wing billionaires who have been interested in controlling information infrastructure, and a newspaper is one of those pieces of infrastructure. And so Patrick Soon-Shiong, I think, for all his faults and for how he's meddled in the editorial and opinion pages at the LA Times, hasn't been as aggressive in interfering with the actual news coverage itself.

If you go look at the actual stories that the journalists are producing there, they're not the kind of stuff that you might necessarily see as a meme on X; it’s still serious work by a lot of the journalists there. So a change of control, where you essentially put trolls in charge of the newspaper could be something that would be very concerning for the hundreds of journalists that remain in that newsroom. And so it's an uncomfortable situation with Patrick Soon-Shiong now, and there is always the possibility that it could get worse.

SL: If this proposal were to go forward, and it doesn't pan out in a way that serves the actual newsroom, we still know that we're left with a problem of finding a sustainable model for journalists to move forward and make a living. But what do you see as some of the potential ways forward for how we can revitalize our industry?

MP: So journalists always, and this has always been true, are going to have to work really hard to figure out what audiences want and cover the stories that are really important to people. You know that kind of innovation, that kind of hard work, that kind of news instinct, is something that will never go away.

A lot of the journalism world has increasingly turned to philanthropy. We've got several solid nonprofit newsrooms in Southern California now. The American Journalism Project is now funding a new nonprofit project in LA, LA Public Press has been picking up a lot of public notice recently, which is really great. But you know, it's all not enough. Like together, there needs to be much more across all sorts of different types of newsrooms across all coverage areas.

The piece that I work on is public policy. California recently attempted to make Google and Meta, these gigantic tech monopolies, help give back some of the trillions of dollars they've made off of all the content on the internet through advertising and data mining. It hasn't been successful yet, but public policy has a role to play. America trails the advanced world in how little we spend in terms of public spending on journalism.

You know, we are a very free market country, and so we leave it to the private sector and to individual people to try to solve our big, structural social problems. But other countries don't do it the same way that we do. We do think there are some lessons to be learned there, and there also needs to be some accountability for having, you know, a handful of huge, huge, huge, like, gigantic companies that control the information that we see and how it's monetized.

"So a change of control, where you essentially put trolls in charge of the newspaper, could be something that would be very concerning for the hundreds of journalists that remain in that newsroom."

-Matt Pearce

SL: What role would you say everyday people, who may not be as familiar with the ins and outs of how we do our jobs, can ensure that journalism remains a public good?

MP: I think personal, individual people can't solve all of our social problems unless they're working together. I will say that if you're an individual person you should have really high standards for the information that you consume. I do think part of the problem is that people have gotten used to consuming slop and junky information from AI or from incitement capitalists who are just spreading misinformation on social media to rack up attention and ad dollars. And I think the public should want better.

It's our brains, it's the most important organ we have. And a lot of people have gotten comfortable just taking garbage in and expecting to get better than garbage out. So on a basic level, you’ve got to want better. It starts there. You’ve also got to organize, support the local newsrooms that you think are covering the community the right way. Support public policies that are going to help those newsrooms survive in an unfair economy that is mostly rigged against journalists and rigged against workers.

I also would say one thing too about cooperative newsrooms, public policy has a role to play in supporting cooperatively owned businesses, where the people who are putting their sweat and blood into these organizations are able to build, sustainable careers and and be able to build some wealth for themselves so that they can retire someday, or they can go have kids and take time off without the whole thing collapsing, which is one of the risks of the creator economy that we're also building, where we're asking people to carry that whole load themselves.

Check out: What does a publicly traded L.A. Times even look like?

Here’s what our reporters have published recently

Abraham Márquez wrote for LA Taco about local elected officials who are financially benefiting from the genocide in Gaza.

He also wrote this analysis piece about Trump’s immigration actions being in line with the US’s racist history towards immigrants.

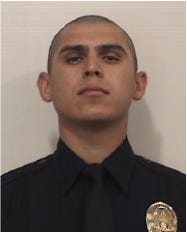

Ben Camacho wrote about a string of incidents Santa Ana Police Department’s (SAPD) killer cop, Luis Casillas, was involved in.

Camacho later published this story about another SAPD cop making a death threat at a traffic stop.

For any inquiries or to give feedback, please contact hello@thesouthlander.com.

You can also find us on:

🦋 Bluesky: @thesouthlander.com

📸 IG: @thesouthlander